Willow Bird

A Red River Métis Short Story

An old man lived with his grown daughter in a small cabin nestled in the bush. Years ago when he was younger, he rode alongside the bison, danced barefoot in the sand while the fiddle sang, and split wood in long rows to last a winter. These days however, his knees rasped, his breath came shallow, and the work of living had grown quiet, but his heart was still strong and it beat mostly for her.

She was sharp as a flint edge, good with a snare, and kinder to others than most of them deserved. Beneath her calm demeanor however, there stirred a quiet upheaval, a deep unrest between who she was at this moment and where she might go.

Some evenings she stood down by the water, her arms crossed and eyes on the horizon, not in longing but in uncertainty. There were letters that sometimes arrived for her from friends and family in the settlement, invitations and promises, but none of it sounded like the rhythm of home.

“I just want things to stay the same,” she once told him. “I want something I can count on.”

The old man nodded, understanding more than he said, but he saw how she struggled. It was in the way her eyes dulled in the quiet hours and how she spoke less these days, not from peace but from something worn thin.

There was a stillness in her that wasn’t rest, but rather it was a loneliness she mistook for contentment. He’d worn the feeling himself, years ago, at a time when the world closed in and he allowed the weight to settle over him until he could no longer move.

As she searched the hush of the land for some small sign, something to tell her she hadn’t lost her way, he said nothing and just stood beside her, so she wouldn’t feel alone in the silence.

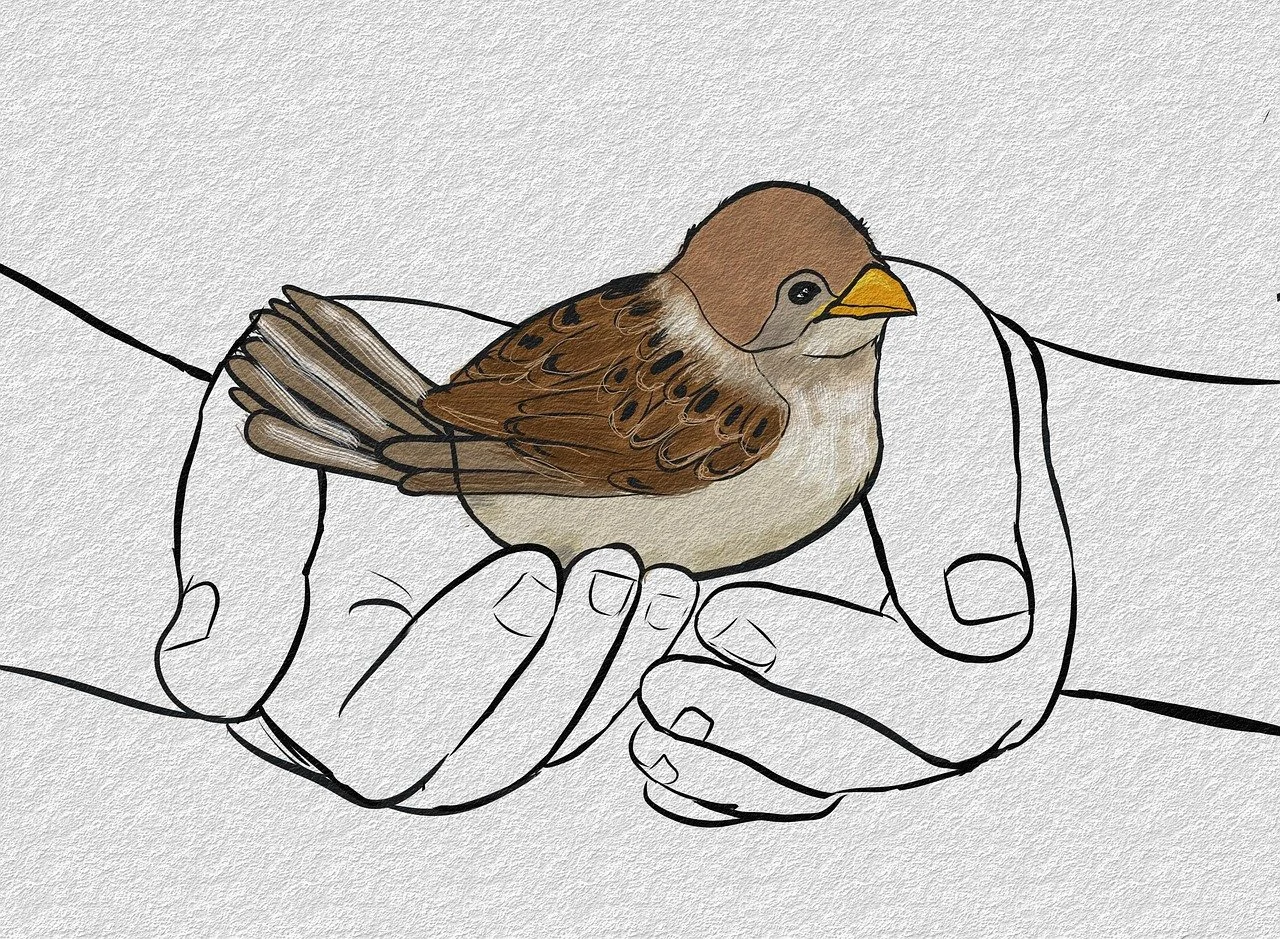

One night, as always, he carved. He made a willow bird from driftwood that had been smoothed by years of current, and she saw it on the windowsill beside his other wooden creatures the following morning.

“Why do you place them all facing outward?” she asked.

“So they know where to travel when the time comes,” he said.

She paused for a moment. “I don’t know if it’s time. Staying right here at home is enough, isn’t it?”

“It might be, but sometimes even the river needs to break its ice to find its path again.”

When spring came and the letter arrived - an opportunity away from the cabin, a life waiting - she hesitated, caught between the safety of what she knew and the pull of what might be. She packed slowly, as if carefully layering memories between the fabric. She took long walks to let the tears flow but held herself steady in front of him. The old man knew what she was holding back. Though he longed to ease her pain by giving her a reason to stay, he understood. It was time for her to go, even though he would be left behind.

The morning she left, he handed her the wooden bird.

“This one,” he said, “was carved for doubt. Its wings are crooked, but it flies true when the wind and everything around it is confused.”

She laughed softly and kissed his cheek, and tucked it into her pack.

She turned and walked toward the trail, once glancing back at the cabin, then again at him, as if asking without words if she was doing the right thing. He smiled and she hesitated for a moment, then faced forward and walked away.

He watched the trees for a long time after, at the place she had descended out of sight at the bend in the trail, although he wasn’t expecting to see her. He wouldn’t insult her strength by hoping that she would return too soon. He kept his eyes fixed on that spot, as if holding the shape of her a moment longer might soften the leaving.

That evening he sat in his chair with a cup of tea, beside the place she used to sit, sock-footed, knees drawn up, reading aloud to him as she did every evening. Her absence was heavy in the room, so he took his knife and began carving the next bird.

This one would be for change, with its wings straight and certain, and for the hope that one day she would be back, not just to fall into familiar habits, but to be more assured in her voice and in her steps and strength. He placed the carving alongside the other creatures on the windowsill but, this time, he left its beak turned just slightly inward, toward the heart of the cabin.